Just as vastness induces awe, so there is wonder to be found in the miniscule. For Dr Roksana Majewska from the Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences at the North-West University (NWU), this is an absolute truth.

Before we zoom in, we need to talk about Hydrophis platurus – or the more friendly sounding yellow-bellied sea snake. This venomous sea snake can be found in all the world’s oceans, except the Atlantic, and is easily spotted because of that distinctive yellow underside. It can also swim backwards, which all other sea snakes without this talent will admit is a very neat and enviable trick.

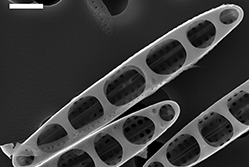

Now, let us narrow our gaze to the microscopic, where we find a one-celled alga with a name that makes Hydrophis platurus look less exotic and even a little bit backward: Nagumoea hydrophicola. It is a diatom, meaning it is part of a large group of aquatic and terrestrial algae and microalgae.

Dr Majewska was the first researcher to discover this diatom, and she found it on a yellow-bellied sea snake.

“It is always so exciting when you look into a new microbial sample. There is a good chance you are going to see something no one else has ever observed. After my previous experiences with sea turtle and manatee diatoms, I did expect I would find some diatoms in there, but I did not expect that this first pilot study would make it so clear that sea snakes also possess their distinct and highly unique diatom flora,” says Dr Majewska about her ground-breaking discovery.

She studied three specimens of yellow-bellied sea snakes at the Port Elizabeth Museum, focusing specifically on what grows on their skin.

What she found by examining the specimens, collected 23 years apart, was that Nagumoea hydrophicola is not only a newly discovered species, it might also be a species that lives specifically on sea snakes.

“What are the chances that, among the hundreds of thousands of diatom species that exist in the ocean, only one would be found in abundance on sea snakes collected 23 years apart from two different locations?”

What are the chances indeed? Her finding also has exciting implications.

Ability to photosynthesise is the key

“This finding suggests that there are microalgae that choose to live on the skin of sea snakes. Isn't that bizarre and intriguing? Diatoms, like plants, have the ability to photosynthesise, in other words, to create organic matter from inorganic ingredients using the energy of light. This means they could potentially live anywhere in the ocean, as long as both light and attachment points are available.”

Thanks to those backward-swimming yellow-bellied sea snakes, these diatoms have a very good chance of growing and thriving.

“For many surface-associated or non-planktonic algae, the problem is that in the open ocean, the only hard surfaces they can attach to exist at the bottom of the ocean, where there is no light. The new findings indicate that some diatom species specialise in living on the surface of their living animal hosts, most likely to avoid competition for hard surfaces and light with other marine organisms,” she explains.

“This also means their fate and survival are inevitably linked to those of their host. Are the skin-associated diatoms important to the snake? Do they have a role in their host's biology? At the moment, we have no idea.”

These diatoms may be tiny, but they hold huge potential: “Such unusual microorganisms must possess special eco-physiological and biochemical adaptations that allow them to thrive on a physiologically active and mobile surface like the sea snake’s skin, where other algae cannot survive. These extreme-habitat microbes are an excellent potential source of, for example, novel bioactive compounds and drugs, including antibiotics.”

Mighty things from small beginnings grow.

|

|

|

| A yellow-bellied sea snake swimming. | Sea snake-associated barnacles (Octolasmis sp.). Scale bar = 1 mm. | |

|

|

|

| Scanning electron microscopy image of the diatom Nagumoea hydrophicola (internal view). Scale bar = 1 µm (micrometre) | Dr Roksana Majewska holding a juvenile lemon shark. |