He strode the red, rich earth of the old Western Transvaal like a colossus, this enigma of a man. Hard and uncompromising, dedicated to the extreme. For decades his name was known in rugby circles the world over as a Goliath of the game.

And I got to wear his blazer once.

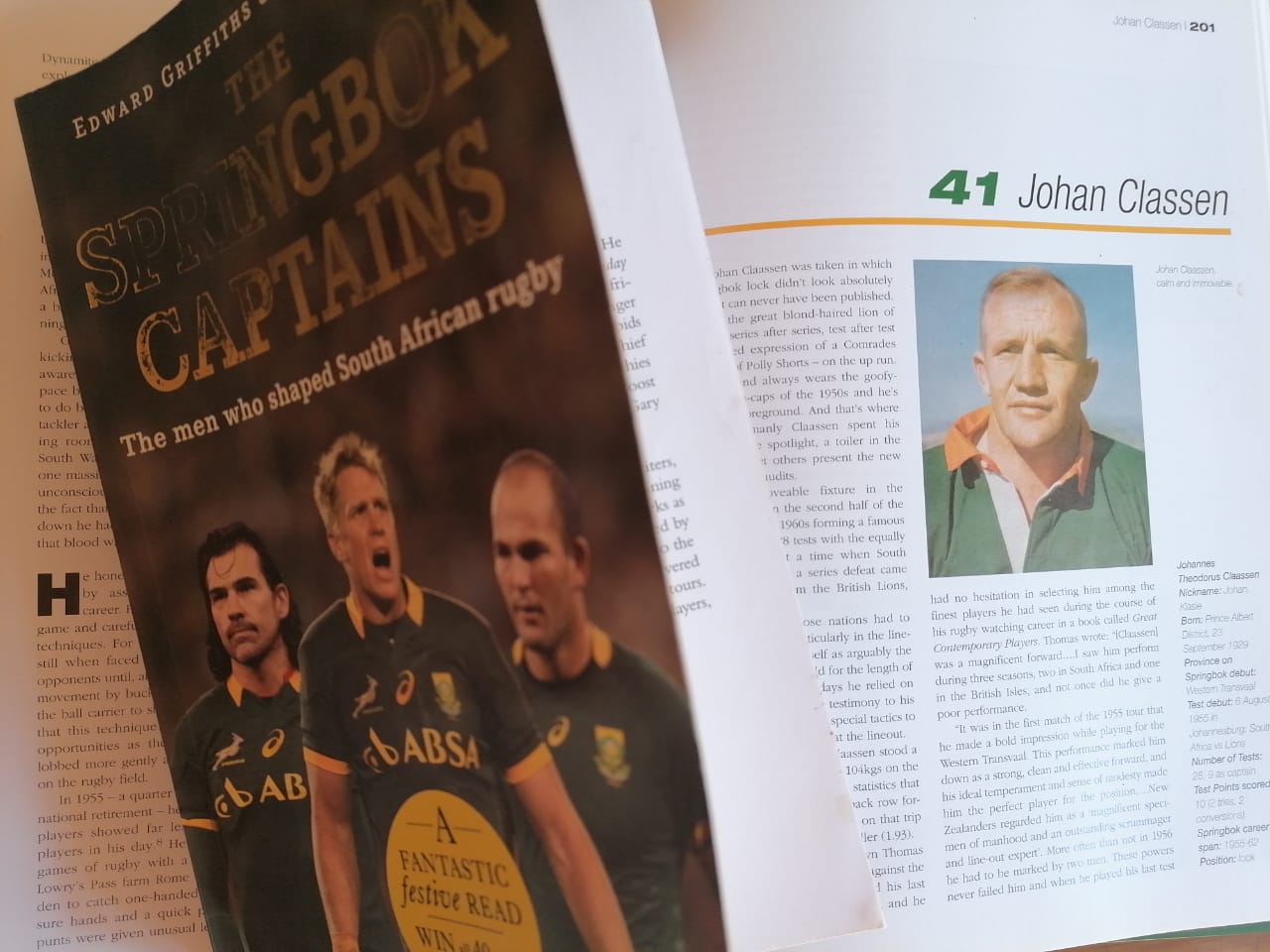

In the amateur days of the sport – when “bricklayer” was your designated vocation and “rugby player” an avocation – Professor Johannes Theodorus Claassen was a pillar of the XV-man code and cast a shadow shorter in reach only than that of Doc Craven. New Zealand’s Player of the 20th Century, Colin “Pine Tree” Meads, called him the greatest lock he had ever played against. Yes, even better than Frik. He was a Springbok player, captain, coach, manager, administrator and selector. Between 1955 and 1962 he played 28 tests for the Springboks and captained them on nine occasions.

And I got to wear his blazer once.

By his own account he was a difficult man, something he came to regret later in life. I know, because he told me so as we sat in his living room in Potchefstroom a few years back. This was not an inaccurate assessment of himself, for that was his reputation, but don’t all men with a singular drive share that trait?

He regaled me with stories about the infamous 1981 flour-bomb tour to New Zealand when the pressure from protestors was unyielding. For safety reasons the Springboks had to sleep at the respective stadiums before tests. This was at the height of apartheid, and the players – many for the first time – experienced the vitriol it evoked from the international community.

During the third and final test in Auckland, Marx Jones and Grant Cole hired a single-engine Cessna 172 armed with flour bombs, flares and anti-tour propaganda. The low-flying aircraft repeatedly circled the pitch, dropping its arsenal and causing havoc. It was war.

He showed me some of his memorabilia, including a drawing of that 1981 touring squad, of which he had been the team manager. He gave me a Springbok pin which, to my ever-lasting regret, I lost.

At least I got to wear his blazer once.

He lived by the tenets of his faith and he expected the virtues he held dear to be reflected by his players and, most importantly, by his captain. He despised boozing, and if he smelled the poison on his players’ breath before practice, he made sure they sweated out every last drop of it through their pores. Prof Claassen was a lecturer in Bible Studies at the then PU for CHE, now the North-West University, and his lifelong affiliation with the institution and with the Western Transvaal rugby union means that, when the NWU Rugby Institute annually announces its best player of the year, that player is awarded the Johan Claassen Trophy.

Prof Claassen passed away in January 2019 at the grand old age of 89. Why then am I remembering him now? The lockdown. For more than 40 days books about the history of Springbok rugby and even the British and Irish Lions have been loyal companions. Prof Claassen has featured prominently in every one of them. The veneration emanating from prose about him is a constant, and I cannot help but remember that day I visited him. I also cannot help remembering the regret he expressed.

As our time together came to an end, we went to his garage. I was hesitant to ask, but he immediately granted my request to put on one of his Springbok blazers. He looked proud as he draped this most sacred of attire over this unworthy imposter’s shoulders.

It is a cherished memory. Prof Johan Claassen may have felt regret, but of this I am sure: no one who was shaped by his influence or had the privilege of receiving his tutelage ever regretted the experience.

By Bertie Jacobs

After Doc Craven, the greatest.