By Gofaone Motsamai

The decline of ArcelorMittal’s operations represents more than a corporate failure; it is a warning of the fragility of South Africa’s productive capacity and the urgent need to restore the country’s industrial base and get back to producing steel.

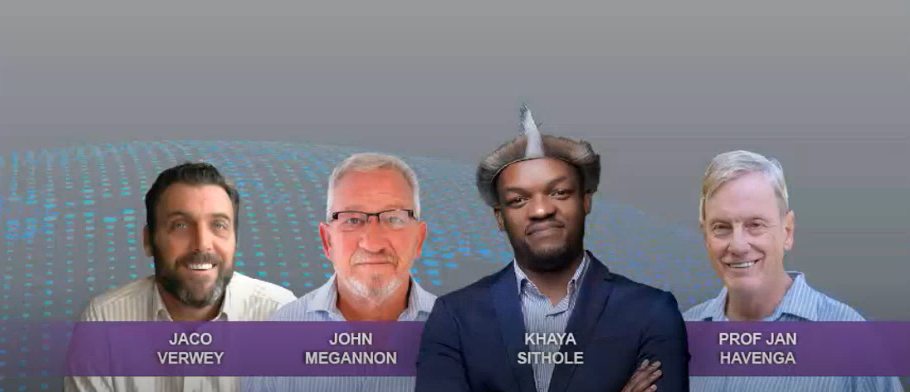

This decline took centre stage when the North-West University (NWU) Business School hosted its latest Pitso discussion on 10 October 2025. The topic, “The closure of ArcelorMittal and the future of manufacturing in South Africa”, saw leading experts unpacking the country’s accelerating deindustrialisation and its far-reaching consequences for employment, infrastructure and economic sovereignty.

The closure of ArcelorMittal’s long-steel plants in Newcastle and Vereeniging has become a symbol of South Africa’s industrial decline. Once at the heart of national development, steel manufacturing now faces severe pressures: high electricity tariffs, crumbling logistics and cheap imports, particularly from China.

The loss of 3 500 direct jobs, alongside many more in supply chains, is not only a local tragedy but also a broader erosion of South Africa’s industrial capacity.

Symptoms of decline

Reflecting on South Africa’s industrial history, Prof Jan Havenga, tenured professor in the Department of Logistics at Stellenbosch University, recalled how post-World War II industrialisation had once been one of the country’s greatest success stories. He noted that enterprises such as Sasol and the Iron and Steel Corporation – later ArcelorMittal, had demonstrated the nation’s ability to transform raw resources into world-class industries.

“I think a lot of the industrialisation was started by government many years ago and led to major success stories,” Prof Havenga said. “South Africa has 80% of the world’s manganese, as well as chrome, coal and iron. We have all the ingredients and more importantly, we have the proven ability to make steel.”

He lamented the current decline, describing it as “unthinkable” that a country with such rich mineral resources and industrial experience would now be importing steel. “A steel industry is one of the shining examples of how successful a country can be. To shut it down is to shut down a part of our capability as a nation,” he added.

Investors are looking elsewhere

Adding a regional perspective, Jaco Verwey, CEO of the Golden Triangle Chamber of Commerce, spoke about the economic ripple effects of the closure on the Vaal region, historically South Africa’s industrial heartland.

“For many years, the Vaal was the industrial hub of South Africa. ArcelorMittal gave birth to many other great industries because it made logistical and economic sense to operate nearby,” he said. “But as infrastructure fails, those advantages disappear. Investors who once wanted to build here are now looking elsewhere.”

Jaco said the closure’s effects extend far beyond the factory gates. “The small engineering shop that relies on ArcelorMittal for 75% or even 100% of its income is now closing down. Each of those shops might employ five or seven people, each supporting up to 17 dependents. The human impact is devastating.”

Systemic weaknesses exposed

For John Megannon, technology and business strategist in mining and AI, the crisis runs deeper than just the steel industry; it exposes systemic weaknesses in the country’s economic structure.

“When you lose a steel plant, you don’t just lose production, you lose the training schools that built our engineers and artisans,” John warned. “We no longer have the ability to develop basic technical skills at scale. Without that foundation, the entire industrial ecosystem begins to collapse.”

He argued that South Africa’s manufacturing and mining sectors suffer from fragmented policy, poor energy planning and weak investor confidence.

“We have vast mineral wealth in the Northern Cape, from iron ore to manganese, but lack the strategic capital to develop it sustainably. Our greatest cost in electricity today is not infrastructure, it’s the legacy of corruption. Until we restore transparency and investor confidence, we’ll keep losing ground.”

Rebuilding infrastructure and trust

All three speakers agreed that South Africa’s path forward depends on restoring its industrial base.

Prof Havenga emphasised that steel production must be treated as a national priority: “If South Korea and China can import their raw minerals and still make their own steel, what excuse do we have? The multiplier effect of domestic steel production on the economy is enormous. We must make our own steel.”

The decline of ArcelorMittal’s operations is a warning about the fragility of South Africa’s productive capacity. Reindustrialisation, the speakers argued, will require not only investment and energy reform but also a renewed social compact to rebuild skills, infrastructure and trust – as a matter of urgency.